ANOTHER PERSPECTIVE ON VERMEER

A few days ago I wondered about different responses to the recent exhibit of 27 Vermeer paintings at the Rijksmuseum in Amsterdam, an exhibit Susie, Todd and I would have tried to see but was sold it by the time we got to the Netherlands.

I mentioned my own emotional response, the intense herd response that I was also caught up in, the response to value determined by scarcity, the objective and academic response of art professionals and then I wondered about the whether digital or printed reproductions might be just as enlivening as seeing the originals in museums.

But a couple of days ago my niece Henny referred a New York Times article to Susie and then on to me. It is entitled Seeing Beyond the Beauty of a Vermeer written by Teju Cole who grew up in Lagos who first encountered Vermeer on the back of a company brochure where there was a reproduction of “The Milkmaid”. It mesmerized him with its beauty. But as he got older he began to see a darker side to Vermeer’s paintings and other Dutch paintings of the period, a dark side which the painters were unaware of.

What he saw in the paintings were the effects of Dutch colonialism and objects which were the direct result of exploitation and often cruelty.

A month or two ago Philip Diehn recommended to our weekly old men’s group a book that had disconcerted him titled The Nutmeg’s Curse by Amitav Ghosh, an Indian writer, now living in New York. I’ve only read a third of the book which is about the origins and rationale of European colonialism. But his first example of how the Dutch East India Company, in order to take over the trade in nutmeg, highly prized in Europe, eliminated the inhabitants of the island Banda in Indonesia was deeply disturbing. It is the horrifying story of how the natives of Banda in Indonesia, refusing to give up their ability to sell the nutmeg grown on their islands in their own way, were treated as being subhuman by the Dutch who felt justified in killing them and destroying their villages when they wouldn’t cooperate.

When I was reading this account I thought of the huge houses we saw around Haarlem including the estate which is now a park where my cousin Henny took us for a lovely walk in a beautiful garden. That house was built on the profits from the tobacco trade. The great wealth of Amsterdam and Haarlem came from the Dutch sea trade including the tobacco trade, the very lucrative trading of slaves world wide and also, trading nutmeg.

It was this great wealth that supported the painting renaisssance of Dutch painters including Rembrandt and Frans Hals and Vermeer.

It is the rich who have usually supported art and often patronized music in Europe and in the United States. There is a direct connection between the robber barons and the great American museums, with the most awful connection being between the Sackler Gallery of Art and the Sackler family’s exploitation of down and out Americans through pushing the opioid crisis. In India the Taj Mahal, a jewel honoring Shah Jehan’s wife, was financed through taxes that in the end exploited the poor. Now the poor wander through it and admire it.

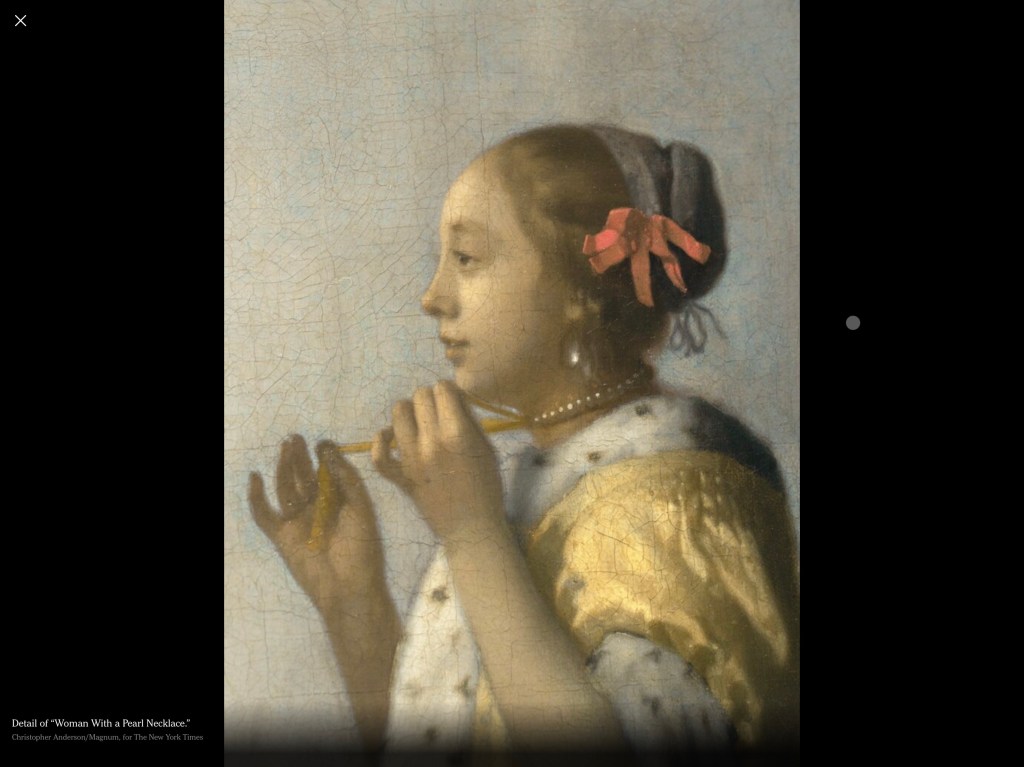

What Teju Cole, well aware of colonial exploitation in his own country, sees in the serene and beautiful paintings by Vermeer are examples of exploitation. The beautiful blue coat of “Woman in Blue Reading a Letter” is painted with ultramarine, a very expensive pigment which came from the mining of lapis lazuli in Afghanistan through probable exploitation of workers. The pearls of “Woman With a Pearl Necklace” were harvested by pearl divers, who worked in hazardous conditions at low pay, in the Gulf of Mannar near Sri Lanka. He gives a number of other examples of luxurious items in the paintings being the result of colonial exploitation.

For Cole the paintings are beautiful and moving, but he can’t help seeing the exploitation which led to the wealth of the Dutch which supported these paintings and the some of the objects which are painted.

The iconic Vermeer painting, “Girl with the Pearl Earring,” has both perspectives, beauty and exploitation.

So what do I do with this knowledge. Yet if I look closer to home I have the same knowledge of a beautiful jacket in an expensive shop in downtown Asheville which was pieced together with handmade materials by young women in a Sri Lankan clothing factory with only a fraction of the price going to the skilled worker and almost all of the profits going to the American distributor and resaler. Or I can look around my house and see so many textiles made by hand in India or Morocco, often one of a kind hangings, for which I paid a very nominal amount to a person who collected them in villages with the woman who made the article receiving very little.

The Dutch profited from trade, but I’m realizing, so do we. Amazon and Target collect goods from around the world and bargain hard for whatever they buy, not too concerned with the lives of the workers, so that the goods can be sold here at a much lower price than if they were produced by American workers. And the exploitation seems to go in both directions, low wages in Sri Lanka and lost wages at the abandoned textile factories around Swannanoa with low wage American workers losing their jobs.

But now this is getting too complicated and painful for me to handle. Becoming aware of Dutch exploitation through past colonialism pains Teju Cole and pains me. But what do I do with that or this new form of American trade. It is hard to call it colonialism but it is American purchasing power that determines what the workers in Sri Lanka will get.

And yet there is another side to this opening up of trade which I have seen in India and is obvious in China. The manufacturing jobs provided by this flattening of the world economic playing field has made life much better for many Chinese and many Indians. The old tariff system hurt everyone but globalization apparently has its risks, too.

So what does an ordinary, only half aware, non economist, 85 year old, me, do with this perspective on Vermeer pointed out by Teju Cole? Sitting here typing, it seems to me I can’t do much even if I knew what to do. My being uncomfortable doesn’t help anyone else very much.

The more I think about this the more questions it raises. The 14 servants, paid very little, my missionary family had in colonial India under the British Raj, the normal thing for missionary families, now makes me uncomfortable. Slavery in the United States, a direct result of colonialism and plantation agriculture and the world wide cotton trade makes me very uncomfortable. The seizing of Native American lands and the removal or killing of the people who lived here in the Swannanoa Valley below my house on “my” land which was theirs, which Ghosh also addresses, makes me very uncomfortable. The shifting weather patterns caused by global warming which leads to people trying to desperately escape to privileged countries where they will be safe (78 died today as a ship loaded with refugees sank off the Greek coast near where I am going to enjoy myself for a month in November). For us these people on the southern border clamoring to live decent lives are more a problem than real people.

So what do I do, or what does anyone do? This is a hole I don’t seem to be able to climb out of and need help.

The June 1st New York Times article can be linked to here:

https://www.nytimes.com/2023/05/25/magazine/vermeer-beauty-brutality.html?smid=nytcore-ios-share&referringSource=articleShare

Seeing Beyond the Beauty of a Vermeer. The photographs come from the same article.