CLOSE TO VERMEER

Susie and I went to a movie at the Fine Arts Theater in downtown Asheville on Sunday afternoon. We wanted to see Close to Vermeer because when we were in Haarlem a few months ago we had planned to go to the Vermeer exhibit, the largest ever, but it was sold out, and, it turned out, so crowded that you had to wait in line behind a crush of people to see each painting. Instead we went to the Frans Hals Museum in Haarlem that wasn’t crowded and saw the same types of Dutch painting, much of it of places in Haarlem like the cathedral, which we saw when there. Frans Hals painted, very realistically, ordinary life in Haarlem and Vermeer painted realistically of Delft. I bought the thick book written for the Vermeer exhibit and have the paintings right here with me.

So this was a chance to quietly attend the exhibit, or rather, to learn how the exhibit was brought together. The star of the show was Pieter Roelops, the curator of the exhibit for whom this was the his crowning achievement just before retiring. He had loved Vermeer since first seeing paintings by him as a boy.

But what struck both Susie and me was the difference between the way that art professionals or rich art collectors look at Vermeer and the way that we do. And I have been wondering since yesterday why I look at paintings the way I do.

I’ve been hooked on painting since I was a boy. This came through my mother, an Illinois farm girl who got hooked on painting after she married my father and left Illinois and traveled the world. She loved going to museums, I knew, although I don’t remember going to museums with her. But she had some art books and put framed reproductions of mostly impressionist paintings on the walls of our house. But we never talked about painting or why she liked a particular painting.

So now looking back I think it was partly knowing her love of painting that influenced me and the books of paintings and the paintings on the walls that introduced me to painting. But what completely hooked me on paintings was the way that painters responded to the world, each in their particular way. It was exactly the same thing that led me to collect books of photography as a teenager which led, finally, after the age of 60 and my first digital camera to my being hooked on taking photographs. It was a combination of the sensual world selected by painters and photographers and their response to what they saw that touched me so intensely and still does. For me some paintings show both an intense emotional response by the painter and elicit an intense emotional response from me that makes me feel very alive. I can’t paint, but the camera lets me photograph and what makes me take a photograph is an intense emotional response, or sometimes even a not very intense emotional response. I’ve been told that I have a good eye, but I don’t think that is true. I see through my eyes but the response is deep in my gut, a jolt of emotional response.

Vermeer does that to me. But then when I think about it more I realize that my taste in art is also influenced by others, in fact, I am part of a herd. When Vermeer suddenly becomes very popular I find myself liking Vermeer more and more simply because other people do. Vermeer was well known in Delft as a painter, but over the centuries he was ignored and now he is suddenly extremely popular. His paintings haven’t changed, the attitude toward them has. They should have touched people as intensely 200 years ago as now, but they didn’t. People 200 years ago barely noticed him and now that so many want to see him, the entire show sold out in a few days. This change in excitement has more to do with herd experience than individual sensitivity.

A second reason that Vermeer is so sought after is that there are only 34 paintings universally attributed to him. Picasso drew and painted prolifically. Up on my wall I have a ceramic made in a workshop overseen by Picasso, bought by my mother in France. I don’t think it is worth $1000. But with only 34 Vermeer’s spread around the world it is very difficult for most people to see more than two or three. And of course the money value of each of the paintings is enormous. Only very rich people can buy them, and as mentioned in the film, the advantage of very rich people buying a painting is that they first take good care of it and then they die, almost always leaving the painting to a museum. Only one Vermeer is in private hands.

So in addition to being touched viscerally by a painting, two other reasons to love a painting is because everyone else does and because it is worth so much. But the film introduced me to another way to approach great art and this was through the eyes of art professionals. Art professionals recognize a Vermeer as great art but in addition they see is as an object made of of canvas and layers of paint in an elegant frame to be studied and conserved.

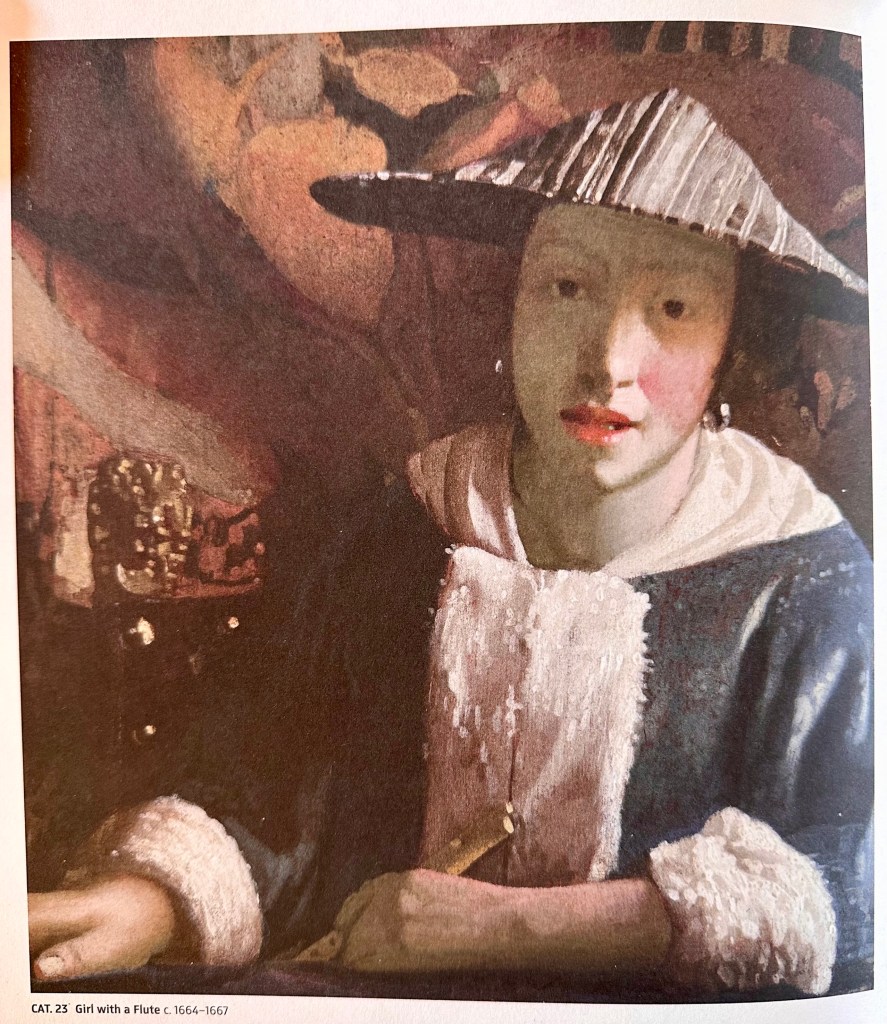

This attitude was seen in the attitude to the painting of Girl With A Flute which was compared to Girl With A Red Hat. Half of the professional art community feels that the Flute painting was painted or finished by someone other than Vermeer and half are sure that Vermeer painted it. They don’t do this by looking at each painting and seeing which gives a bigger emotional jolt, as I would. Instead they look at the quality of the brush strokes and the amount of green in the shadow on her neck. And when looked at this way, the painting is either a beautiful painting with extremely high value or an ordinary painting, hardly worthy of interest and having very low value. Pieter Rollmops, the elderly curator in love with Vermeer is torn. On one hand his emotional response values the painting, while his objective scientific side, if the painting proves to be by someone else, rejects the painting. In the end the painting was voted into the exhibit.

So this is a fourth way of viewing a painting. First is the individual jolt of intensity the painting provides, second is the herd feeling that the painting is a great painting, third is the scarcity value and the degree to which other people want the painting that sets the price at auction, and fourth is this objective scientific study of the painting as stretched canvas and layers of paint.

But where does this leave me? It leaves me with the jolt that I feel when I see a painting, influenced I know by the herd evaluation. But in this case the Girl With A Flute touches me with just as much intensity as the Girl With The Red Hat. They both knock me out equally and are equally valuable to me.

But setting me apart from Thomas Kaplan, the collector, who owns the one private Vermeer not in a museum, I am just as touched by a reproduction of Vermeer, actually either on paper or a digital version on the screen, as I am by the original for several reasons. One is because seeing a Vermeer in a museum, even the exhibit of the century in Amsterdam would have been both annoying because of the crush of people and, on my elderly legs, tiring. After a little I would have wanted to sit down. A second reason reproductions appeal to me is because printing improvements can now make the reproduction of a painting so precise that you can’t tell the difference between the original and the reproduction. My emotional response, which is what really matters to me, not the money value of the painting, is the same for each. And the reason that I like the digital version is that on a screen on my wall I can look at hundreds, even thousands, of paintings and I find changing the painting every 30 seconds or ten minutes allows variety and enhances my appreciation of each painting. Another reason for appreciating the reproduction as much as the original is that the original is only there for ten minutes of viewing in a museum or, or in the case of Thomas Kaplan’s collection is only there for him and his dinner guests. Reproductions allow the whole world, if they are interested to be touched by Vermeer’s vision of the world.

But this leaves the professional art handler’s response. While I find what they can tell by X-ray the levels of paint and can identify the roll of canvas used in various paintings, that objective, scientific focus actually diminishes my delight in the painting. Professionals can interpret every aspect of a painting, guessing at the artist’s intentions, telling us what Vermeer intended to do and how he did it, with a camera obscure or not. First of all, I really don’t care that much about their fine distinctions and secondly I don’t believe half of what they say. But thirdly, I find that that intense academic way of sorting and interpreting art actually diminishes my pleasure in a painting or distracts from it. I find the same to be true of much of the academic interpretation and evaluation of poetry and plays and novels. I find it to be true of critical responses to music. I find it to be true of a lot of academic learning which can stifle as much as it brings delight. Some people going to college enjoy learning in this way and fitting into an academic discipline with all of its conventions. But many young people who go to college don’t.

I don’t know quite where this leaves me. But the response that means the most to me is the response I felt as a boy when I first was introduced to painting and photography. And even now, the pleasure I find in making photographs is completely emotional. Maybe it is because I am too simple or there is some complexity missing in my photographing. Maybe I am missing out on something. But for me, anyway, I had plenty of time in graduate schools to discover that academic delight, and I never did.