CLUELESSNESS

This is probably my twentieth time or more to visit Varanasi. And it is probably close to my tenth longer stay of two weeks to a month and the fourth stay at the Sahi River Guest House. And I am realizing how clueless I am about India, and by extension to the other places that I am been visiting for longer periods this year: London, Paris, Winsen, Essouira. And by further extension, my cluelessness about the United States.

A few days ago when I approached a cycle rickshaw driver for a ride to take photographs to Khanija Studio to be printed the little guy who pedaled my rickshaw to Lanka was overly cheerful and excited about taking me and instantly accepted my 100 rupees round trip offer without bargaining, which has always been the case.

Yesterday afternoon I met him again when I went to the Ramesh Singh Boundary to deliver the photos and to take some more. There he was again with his cycle rickshaw and his family. I had taken photographs of him before and he counted me as an old friend and in my cluelessness I hadn’t recognized him and with my poor Hindi hadn’t understood him. I now took many more photographs of his family and then Susie and I were invited into his house for sweet milky chai and crackers that he gotten somewhere.

He brought out a framed larger photograph of him and his family that I had made four years ago when I offered them to any family that wanted one, and then his wife brought out a board with photographs I had taken of their family six or eight years ago when I sat with children around a huge bonfire at the lower end of the compound as they celebrated Holi.

But all of this I discovered slowly as I took photographs and then drank tea. I realized how little I was aware about anything going on in Ramesh Singh Boundary. Part of this is because of my broken Hindi. I can talk about the weather or say that something is beautiful or tastes good or is too expensive. But when it comes to really understanding family relations or things that really matter to someone living in the Ramesh Singh Boundary, I am almost clueless. And it isn’t just language. It is a difference in culture that is so wide that I am blinded by my own American preconceptions. I misinterpret everything.

When I try to get a family photograph, a nuclear family photographs in narrow American terms, I first get an older man and woman and three kids in front of me but then more and more adults and children pile in until I have 15 people in the photograph and more joining. For Boundary people family is extended family. Almost the whole of the compound, twenty or thirty small makeshift one room houses seem to house family.

I do know that they are a Bengali community and outsiders in Varanasi. They all speak Bengali and all speak Hindi and many speak a little English, the most universal of Indian languages.

And I am vaguely aware that the women all married into these families from somewhere else while all of the boys and men remain here in this community just as they would do in Indian village life.

But I completely misconceptualized everything about the little girl who six years ago was racing around on Holi smearing herself and others with colored paste, and four years ago took me to her school and invited me right in so that the principal and teachers all allowed me to photograph their classes. I then, before I left, gave her the framed photographs to deliver to the school.

I was expecting her at fifteen or so to be attending a secondary school. She was bright and alert and took school very seriously. Maybe she would go on to college and be successful at a career.

Those vague thoughts were in my head. So when I was told by the wife of one of the sons of the cycle rickshaw driver that the girl had been married at 13, 14 or 15 just as she, herself, had been I felt my cluelessness and realized I was living in a fantasy world. “We are poor people,” she said. “What else can we do?” She was resigned to her life and to the life that this bright little girl, probably already pregnant, was going to have. She would have several children and then in middle age would become the matriarch of her own family with girls from somewhere else being found for her sons and her daughters being married away at great expense.

In the streets we have seen a number of wedding parties on the way to the wedding party plots where at great expense a boy and a girl, or a man and a woman, who barely know each other, brought together in an arranged marriage by parents, are joined in an elaborate union of two families. And down our street each day a groom and his new wife are announced by drummers in front of them and family trailing behind them as they come to do the ritual prayers that will allow them to be united sexually.

I have seen this, just as I’ve seen bodies being taken to cremation, wrapped in gold cloth, on the shoulders of family. But I haven’t really comprehended what I vaguely understand. I don’t comprehend what it is to be Indian, particularly lower class or poor Indian. I am clueless.

So after taking a large number of photographs Susie and I were invited into the house of the cycle rickshaw family. They lived with a brother’s family in two rear rooms, each about ten feet by ten feet, with one shared outer room where they can cook on a gas stove. There must be a shared toilet or two for the whole community and dishes and clothes are washed at a shared outdoor faucet in a wash area at the upper end of the compound.

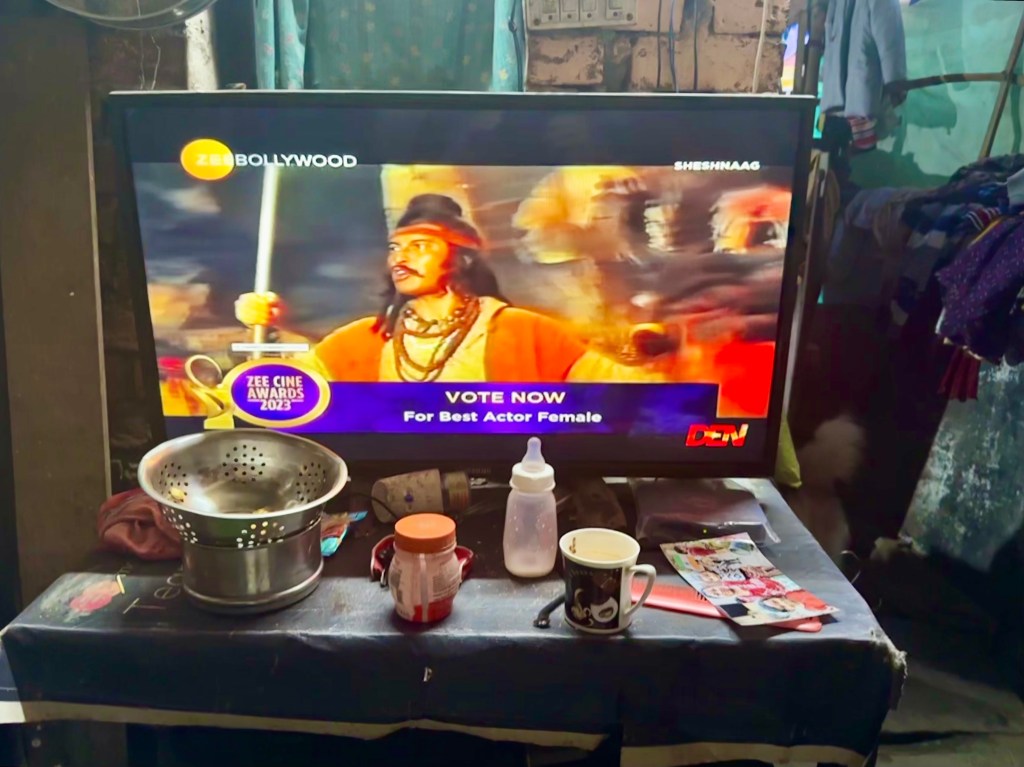

In the inner family room was a large bed in which everyone sleeps, an elmirah or wardrobe, where clothes were kept, some photographs on a shelf including the ones I had made and incongruously a second hand flat screen 30 inch tv on which a Bollywood film was playing. They also had cell phones. Also within the house were three pet white rabbits, two brown ducks, and a family dog all amicably sharing the space.

There was certainly no privacy inside the one family room or outside of it in the compound. There were twenty or thirty kids playing in the narrow walkway between the houses. What there was is a large friendly community which all seemed to be supportive of each other, a huge extended family, none of whom owned very much.

How could they be so friendly and apparently happy? I certainly don’t feel sorry for them.

And I don’t feel they were jealous of my huge wealth (I am aware of how rich, rich, rich I am) and freedom to travel and endless years of education and a culture that with a safety net beyond their wildest dreams. ((The rickshaw driver is missing his front teeth, here in India I am paying thousands of dollars to implant missing teeth). They also didn’t seem embarrassed about their tiny house or meager means.

I think back to the other cycle rickshaw rides I have taken and how I bargained every time, not wanting to be cheated, with men who would only earn the equivalent of 75 cents for ride back and forth to Lanka and who would earn only a few dollars a day in rupees to feed and support a family of six or ten. The cycle rickshaw drivers are lower in the hierarchy to the motorcycle rickshaw drivers, who rank below those with larger motor cycle rickshaws who run a route picking up and dropping passengers for a small fee, more like a bus service. And above them are the taxi cab drivers who are mainly around the train station. People who have means will have a motorcycle that can carry four adults and a couple of children as the family vehicle. And the very rich will have cars or SUV’s which don’t move any faster in the dense Varanasi traffic than a bicycle.

So the bicycle rickshaw drivers are constrained by the competition with other rickshaw drivers and the faster motorcycle rickshaws and so have little bargaining power and have to eke out a living. Of course they bargain every time they offer a ride.

This is the life of the girl who led me to her school on her bicycle and who is now married and about to have the first of several children. She is probably married into a family where her husband will be a boatman or cycle rickshaw driver or hotel worker. She will be absorbed into a joint extended family which will support each other and will finally be her support in her old age, her social security blanket. At this point she will be under the thumb of her mother-in-law and in the distant future will be the martriarchal monther-in-law herself.

All of this I sort of understand but don’t really understand at all. I am caught in my own American preconceptions of what life is about and my misconceptions of what life is about for Indians with few prospects or means. All of the children in the Ramesh Singh Boundary have school uniforms and go to school because it is the one way out of poverty. All Indians, unlike many Americans, are very serious about getting a good education. But the path out of povery to a better life in India is very difficult.

I know in the Ramesh Singh Boundary, there must be many tensions below the surface that an outsider, particularly a clueless American outsider, isn’t aware of. But on the surface I feel a sense of community and mutual support that seems good to me. And of course on the opposite side, the people I met yesterday are aware of what my circumstances are but they must be as clueless about what it is to be an American as I am clueless about them. But while sitting on a stool drinking sweet tea and eating crackers I also felt a closeness and an acceptance that felt good. I will carry both feelings, closeness and cluelessness, away with me.